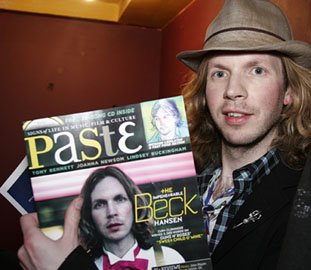

Paste magazine launch party with Beck

So, while my girls trotted off to their expensive arena seats I sat at home in front of the computer. Bored and a little irritated with my situation, I perused some music sites and stumbled upon a Web competition from Paste. They were giving away tickets to the 26th issue launch party at the Knitting Factory. Conincidentally the issue features Beck on the cover, (a sore subject for me), but what the hell, I’ll fill out the form. I never expected to win.

***

When I arrive at Leonard Street around 8 p.m. knots of people stand behind a velvet rope puffing on butts. It wasn’t an exclusivity thing; apparently the club has had trouble with the neighbors. It might have something to do with all the construction on both sides of the street, little room for traffic, less for smokers. A check of my ID, an eye locating my name on the guest list and I’m in.

The main room and its adjoining area are already packed with wannabe rock stars, writers and Paste personnel. I cop a drink and move towards the main stage as the NYC-based folk/alt-country act Hem mount the stage. Singer Sally Ellyson’s voice is sweet enough, but her protruding stomach proves an unconquerable distraction. Seven and half months pregnant, you have to give the woman respect for crooning in that condition, the blandness of the band, however, deserves few if any props.

At this point I’m wondering why I bothered to show up. Sure, the tickets were free, but my roommate is super late and I’ve been standing around by myself for an hour and half. I’ve only had a few blips of conversation with other partygoers and Hem’s adult contemporary sound is just not doing it for me. I decide to have one more drink and peace out. Matt finally shows up and we order two beers.

Halfway through our Sierra Nevada and Heineken, stage hands start to assemble the stage for the next surprise band. It took an unusually long time to complete sound check and considering how disappointed I was with the first act, I vowed to be out after I swallowed the last sip of my pale ale. Who wants to stick around for a group that probably sucks as much as the last one, especially when they’re pretentious enough to take 40 minutes setting up?

At last the Paste host ambles up to the mike to announce the special guest. After tipping his hat to Questlove who had filled dead air with various guitar driven dance jams during intermissions, he said, “We here at Paste are pleased to introduce Beck!” Are you serious? Beck is playing in this small club for 150 people when the previous week he sold out the theater at the Garden? Do I hear Lady Luck shuffling in a 180 degree rotation? Well, I at least see Beck emerge from the side room and that’s proof enough for me.

Without scrims or massive video screens, without lasers or scantily clad dancers, Beck and his band plow through songs from his newest release The Information right down to Mellow Gold. After coursing through a few selections, Beck asks the audience for requests. Inexhaustible answers spring from the crowd as Matt chimes in with a booming “Devil’s Haircut.” Beck looks him directly in the eye and strums the opening chords. At that moment, Beck doesn’t play for Paste, he plays for us.

The band -- composed of a fro-ed out hipster bass player (name) with white latex pants and matching sunglasses, a percussion/dancer (name) in brick red jeans, a keyboard/sideman (Brian LeBarton ) with a pageboy haircut, a drummer (Matt Sherrod ) hitting the skins so hard the snare popps up and down and a too-cool-for-school guitar player (name) who munches on gum like cud and stands aloofly in the same spot all night – played a professional set, yet seemed to take the experience rather lightly.

***

It’s probably been ages since Beck and his band played small club. I imagine the show provided a certain leeway that performing in front of thousands of people doesn’t allow. After Beck left the stage, the band stayed on to a do an original song with the degrading and repetitive chorus “drop your panties to the floor.” No one, of course, followed their commands, but it was a light touch on an otherwise thoughtful set.

On the way out I reveled in my good fortune and relished the opportunity to call my friends and tell them about the free Beck show. As I was entering the final corridor, a face struck me as familiar. I realized it was James Iha, former guitarist for the Smashing Pumpkins. I sent my roommate in to snap a shot. I’m still broke, but at least I have a story to tell and a picture to prove it.